Study exploring the idea of biological fatherhood in historical Europe reveals that 1 to 2% of children in each generation are the products of extramarital affairs. The likelihood of having an affair was influenced by both socioeconomic status and the density of people living around them.

Biological fatherhood

In an age where paternity tests are readily available at any drug store, we are all well aware of cheating, infidelity and extramarital sex. We have grown accustom to the idea of extra-pair paternity (EPP) and accept that there are fathers unknowingly rearing children who are not ‘biologically’ their own. But, how about our ancestors? Was cheating a common occurrence in our past?

In this first large-scale study of its kind this was exactly question researchers were interested in. Has cheating always been the ‘norm,’ and if so what factors affect the likelihood of infidelity? So, they choose to make use of genealogical data paired with DNA tests to look at how social context can influence our behaviour, specifically extra-pair paternity or extra-marital sex.

Paternal lineage and the Y chromosome

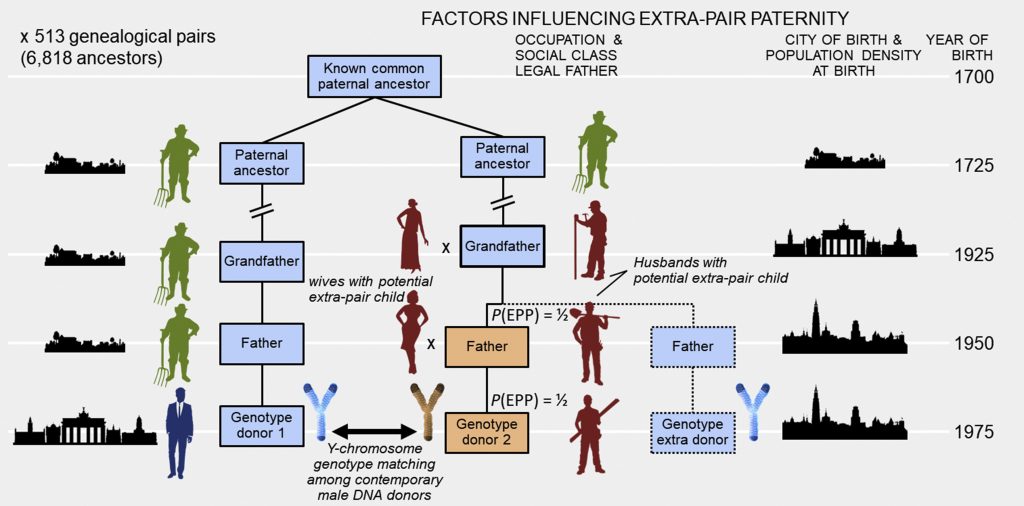

The study involved 513 pairs of men who living in Belgium and Netherlands born between 1750 and 1950. The pairs were identified by looking at genealogical records (marriage and birth records for example) of 6,818 male ancestors. Based on genealogy they shared a common paternal ancestor.

The next stage involved DNA analyses of the Y chromosome. Because the Y chromosome is passed down from father-to-son along the paternal line, you would expect two related men to have the same Y chromosome. So in an idea scenario where there are no incidents of infidelity through the generations the Y-DNA profiles of all 513 pairs would match each other.

Social context matters

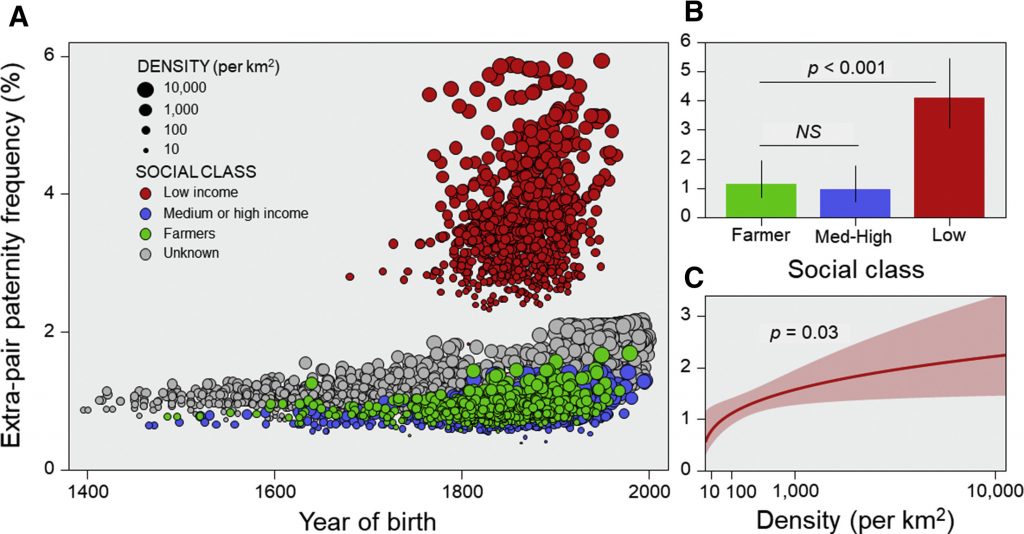

What did they find? On average extra-marital paternity was fairly low. Only 1-2% of children in each generation had mismatched Y-DNA profiles therefore were classified as being a product of extra-marital pairing. Religious affiliations didn’t seem to affect the rates of infidelity, as it was quite similar between Belgium (predominantly Catholic) and Netherlands (mostly Protestant).

Quite surprisingly however, the frequency of extra-marital paternity depended heavily on social context. EPP rates were much lower in those who belong to higher socioeconomic classes such as the farmers, skilled craftsmen and merchants (~1%), while it was much higher in the lower economic classes (labourers and weavers) at approximately 4%.

What’s more, incidents of EPP increased with population density. The rates were much lower in areas that corresponded to sparsely populated rural villages (~0.6%) compared to those living in densely populated cities (2.3%).

These differences were even more pronounced when socioeconomic status and population density were combined ranging from 0.5% in middle to high class farmers living in sparsely populated villages to 6% in those of lower social classes living in densely populated cities.

Opportunistic cheating

Scientifically speaking, it is more advantageous for a male to have multiple partners. This increases their genetic fitness or the likelihood of passing down their genetic material to as many offspring as possible. Women also benefit from pairing with genetically superior males.

But how does this biological observation fit into what was found in this study? One possibility is when faced with more stressful social and economic circumstances women find more value in extra-pair mates, because they can provide additional resources or social benefits. On the flip side, perhaps fathers in lower social classes are less likely to prevent cheating, because they don’t to worry about wealth (in terms of land for example) that will be pass on to their offspring.

Making the link from genealogy to social behaviour

What ever the explanation may be, this study gives us interesting insights into how factors like social context has a very strong influence on social behaviours. Even more important perhaps, is the connection it draws between genetic genealogy and the study of human evolution and behaviours.

This means that not only does DNA allow us to trace our roots to discover our ancestors, but it also provides us a portal into discovering how factors like social context, religious and political affiliations and economical turmoil may have shaped the behaviour of our ancestors, which would impact the evolution of the human race as a whole.

Reference

A Historical-Genetic Reconstruction of Human Extra-Pair Paternity